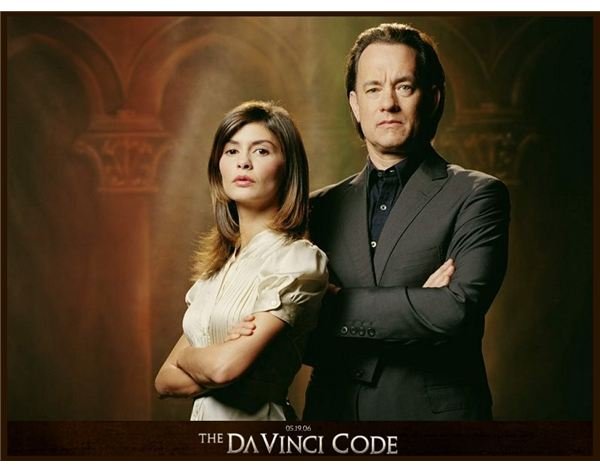

The Da Vinci Code

The Da Vinci Code is a 2003 mystery thriller novel by Dan Brown. It follows 'symbologist' Robert Langdon and cryptologist Sophie Neveu after a murder in the Louvre.

Common Sense Note Parents need to know that the movie opens with a brutal murder and includes several other bloody scenes, including a naked man beating himself. The subject matter is too convoluted to interest young kids, so unless you want to shush them, leave them home.

A couple of characters use mild profanity, although most of the cursing shows up in French and in subtitles. SPOILER ALERT: The film's plot, based on Dan Brown's best-selling novel, suggests that the Catholic Church has for centuries repressed the 'truth' that Jesus was human, married Mary Magdalene, and fathered a daughter. Some viewers may find the issues raised - Jesus' divinity and the Church's cover-up - upsetting. Sexual Content Some famous paintings show women's naked body parts; Silas appears naked as he performs self-flagellation (you see only his backside and close-ups of limbs); discussion of gender roles includes mention of penises (emblem of 'male aggression'). Violence Shooting murder opens the film; Silas whips and cuts himself, showing blood and cringing/grimacing in pain; grainy flashback scenes repeatedly show violence (Crusades/knights, battles/armies, witch hunts/burnings, visualizing various narrations of 'history'); personal flashbacks include Silas' abuse as a child, young Robert trapped in a well, and young Sophie crying/afraid in the harrowing car accident that killed her parents. General action includes shootings, fisticuffs, poisoning, kicks/slaps; Silas kills a nun by smashing her head; blood on shirts and faces. Language Some swearing, including French with subtitles ('s-t,' 'bastard') and English ('Jesus,' 'hell').

The Da Vinci Code 2

Social Behavior To protect a secret, characters kill, lie, rob, and injure - while others are determined to uncover the truth. The movie's plot presumes upon long-standing, deep-seated cover ups among very important people. Consumerism Not applicable Drugs / Tobacco / Alcohol Not applicable.

Correction Appended Fearing that the best-selling novel 'The Da Vinci Code' may be sowing doubt about basic Christian beliefs, a host of Christian churches, clergy members and Bible scholars are rushing to rebut it. In 13 months, readers have bought more than six million copies of the book, a historical thriller that claims Christianity was founded on a cover-up - that the church has conspired for centuries to hide evidence that Jesus was a mere mortal, married Mary Magdalene and had children whose descendants live in France. Word that the director Ron Howard is making a movie based on the book has intensified the critics' urgency.

The Da Vinci Code Full Movie

More than 10 books are being released, most in April and May, with titles that promise to break, crack, unlock or decode 'The Da Vinci Code.' ' Churches are offering pamphlets and study guides for readers who may have been prompted by the novel to question their faith.

Large audiences are showing up for Da Vinci Code lectures and sermons. 'Because this book is such a direct attack against the foundation of the Christian faith, it's important that we speak out,' said the Rev. Lutzer, author of 'The Da Vinci Deception' and senior pastor of Moody Church in Chicago, an influential evangelical pulpit.

Among 'The Da Vinci Code' critics are evangelical Protestants and Roman Catholics who regard the novel, which is laced with passages celebrating feminism, anticlericalism and pagan forms of worship, as another infiltration by liberal cultural warriors. They also say it exploits public distrust of the Roman Catholic Church in the aftermath of the scandal involving sexual abuse by members of the clergy. The debunking books range from scholarly hardcovers to slim study guides.

Among the publishers are well-known Christian houses like Tyndale and Thomas Nelson and less-familiar outfits. Since most of the books have either appeared in stores very recently or have not yet been published, it is too early to say how they are selling. The critics and their publishers are also hoping to surf the wave of success of 'The Da Vinci Code,' which has been on The New York Times hardcover fiction best seller list for 56 weeks. There are 7.2 million copies of the book, published by Doubleday, now in print. Of the 10 new Da Vinci-related books, eight are by Christian publishers. One evangelical Christian publisher, Tyndale House, which hit gold with the 'Left Behind' books, is about to issue not one but two titles rebutting 'The Da Vinci Code.' ' Dan Brown, the former teacher who wrote 'The Da Vinci Code,' is declining all interview requests, his publisher says, because he is at work on his next book.

The buttons below will download the X-Plane 9 updater. Running this will upgrade your existing copy of X-Plane 9 to the final version of X-Plane 9. X plane 9 free.

Brown says on his Web site that he welcomes the scholarly debates over his book. He says that while it is a work of fiction, 'it is my own personal belief that the theories discussed by these characters have merit.' ' 'The Da Vinci Code' taps into growing public fascination with the origins of Christianity.

More scholars have been writing popular books about the relatively recent, tantalizing archaeological discoveries of Gnostic gospels and texts that offer insights into early Christians whose beliefs departed from the Gospels in the New Testament. The plot of 'The Da Vinci Code' is a twist on the ancient search for the Holy Grail. Robert Langdon, portrayed as a brilliant Harvard professor of 'symbology,' and Sophie Neveu, a gorgeous Parisian police cryptographer, team up to decipher a trail of clues left behind by the murdered curator at the Louvre Museum, who turns out to be Ms.

Neveu's grandfather. The pair discover that the grandfather had inherited Leonardo da Vinci's mantle as the head of a secret society. The society guards the Holy Grail, which is not a chalice, but is instead the proof of Jesus and Mary Magdalene's conjugal relationship; Langdon and Neveu must race the killer to find it.

Along the way they learn that the church has suppressed 80 early gospels that denied the divinity of Jesus, elevated Mary Magdalene to a leader among the apostles and celebrated the worship of female wisdom and sexuality. Advertisement The novel, in which even chapters only two pages long end with a cliffhanger, might seem like little more than a potboiler. But it opens with a page titled 'Fact.' ' That page concludes: 'All descriptions of artwork, architecture, documents, and secret rituals in this novel are accurate.' ' The book portrays Opus Dei, a conservative network of Catholic priests and laity, as a sinister and sadistic sect. In it, an albino Opus Dei monk assassinates four people who guard the secret about the union of Jesus and Mary Magdalene.

The Da Vinci Code Sequel

The real Opus Dei has posted a lengthy response to 'The Da Vinci Code' on its Web site, warning, 'It would be irresponsible to form any opinion of Opus Dei based on reading 'The Da Vinci Code.' Our Sunday Visitor, the Catholic publishing company, has published a book and a pamphlet offering a Catholic response to the book. The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America has also issued its own guide. One reader, Rob Bellinger, 22, who was raised Catholic and attended Jesuit schools in New York City, read 'The Da Vinci Code' and said, 'I don't believe it's 100 percent factual, but it did get me thinking about a lot of things.' ' For example, Mr. Bellinger said, 'if you just look at the contemporary church, it's really hard not to raise questions,' like why no women are priests. Though for many readers the notions about Christian history in 'The Da Vinci Code' seem new and startling, the novel introduces to a popular audience some of the debates that have gripped scholars of early Christian history for decades.

The academic chatter grew louder after the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls in the 1950's and of ancient texts in Nag Hammadi, Egypt, in 1945. Among the findings were early Christian scriptures and fragments not included in the New Testament, including writings that scholars have come to call the 'Gospels' of Mary, Peter, Philip, Thomas and Q.

'The Da Vinci Code' floats the notion that the fourth-century Roman emperor Constantine suppressed the earlier gospels for political reasons and imposed the doctrine of the divinity of Christ at the Council of Nicaea in A.D. A character in 'The Da Vinci Code' points out that it is history's winners who get to write history, a refrain echoed by Mr. Brown on his Web site.

Comments are closed.